The Empty Threat of a World Cup Boycott

Boycotts demand backbone, moral clarity, and a willingness to absorb real costs. European leaders have shown, time and again, that they possess none of the three.

Welcome to Sports Politika, a media venture founded by investigative journalist and researcher Karim Zidan that strives to help you understand how sports and politics shape the world around us. My mission is to offer an independent platform for accessible journalism that raises awareness and empowers understanding.

If you share this vision, please consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber.

“Stay away from the USA!”

This was the specific phrase uttered by Mark Pieth, a Swiss attorney and corruption expert who chaired the Independent Governance Committee which oversaw FIFA’s reform between 2011 and 2013, during a recent interview about the 2026 World Cup.

“What we are seeing domestically—the marginalization of political opponents, abuses by immigration services—doesn’t exactly encourage fans to go there,” Pieth continued in his interview with Swiss newspaper Der Bund. “You’ll see it better on TV anyway. And upon arrival, fans should expect that if they don’t please the officials, they’ll be put straight on the next flight home. If they’re lucky.”

Pieth is right. Since taking office in January 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump and his revamped administration have pursued a dramatic reorientation of both domestic and foreign policy. This shift has included misguided tariff policies and sweeping visa bans, imperialist ambitions toward Canada, Greenland, and Venezuela, and a violent crackdown on immigrants that has resulted in the killing of two Americans by federal agents.

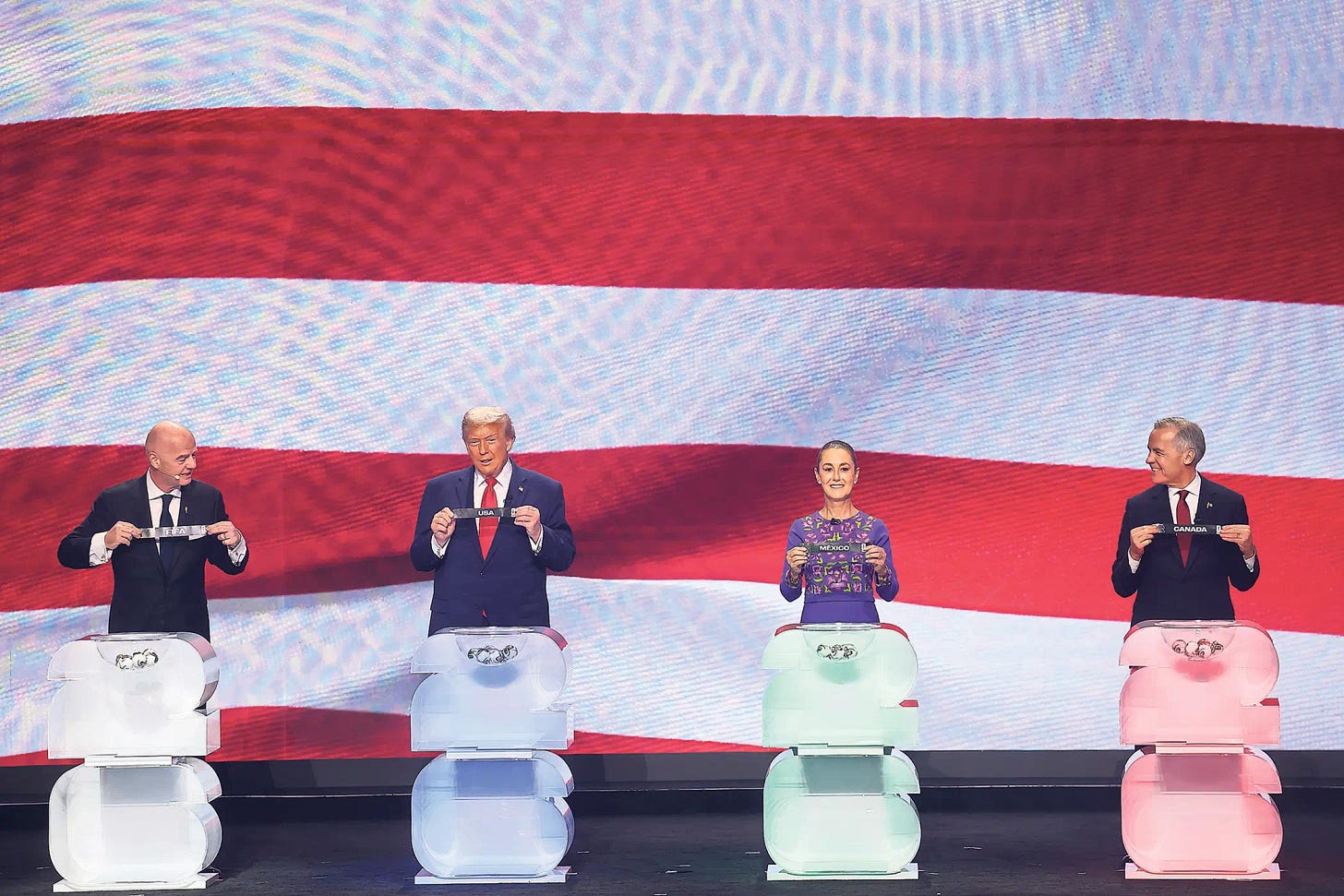

As the U.S. prepares to co-host the 2026 World Cup alongside Canada and Mexico this summer, calls for a boycott of the world’s biggest sporting event have gained traction among prominent figures in international football. Former FIFA President Sepp Blatter backed Pieth’s comment on X, adding “I think Mark Pieth is right to question this World Cup.”

Blatter stepped down as FIFA president in 2015 amid several scandals and was replaced by current boss Gianni Infantino. He was acquitted last year on charges stemming from a delayed payment of two million Swiss francs ($2.5 million) FIFA made to French football legend Michel Platini in 2011 for consultancy services.

European lawmakers have also backed calls for a boycott. German Member of Parliament Jürgen Hardt told tabloid Bild that Germany’s national football team might consider skipping the tournament “as a last resort” to bring Trump “to his senses.” Another German MP echoed Hardt, adding that he has a “hard time imagining that European countries would take part in the World Cup.”

Oke Göttlich, a vice president of the German soccer federation, said in an interview last week that it was time to “seriously consider and discuss” a boycott similar to the Olympic boycotts during the Cold War.

“What were the justifications for the boycotts of the Olympic Games in the 1980s?” Göttlich said. “By my reckoning, the potential threat is greater now than it was then. We need to have this discussion.”

Göttlich’s intentions may be well meaning, but his underlying premise is fundamentally flawed. While Europe is fully within its rights to threaten a boycott of the United States, likening such a move to the Cold War–era Olympic boycotts—among the least effective in the history of international sport—ultimately undermines the argument.

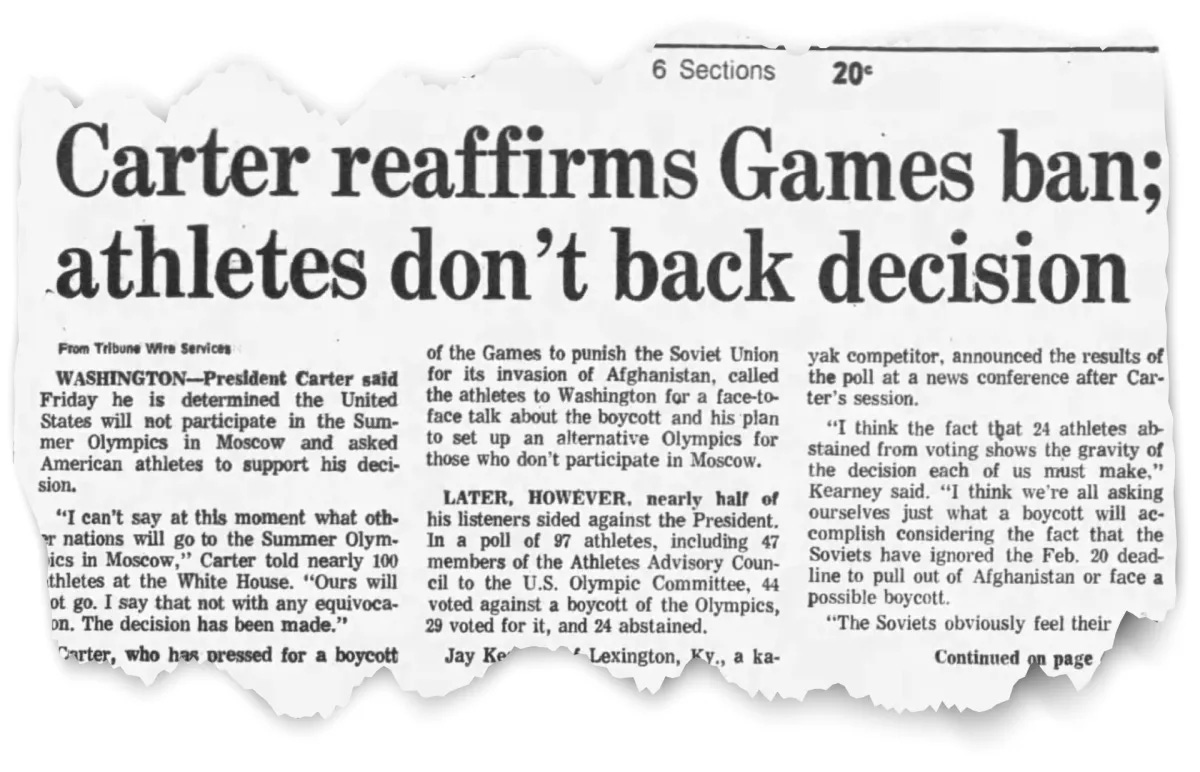

On March 21, 1980, U.S. President Jimmy Carter announced the US would boycott the 1980 Summer Games in Moscow to protest against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. This marked the first of numerous times that the two superpowers would use boycotts as part of their political arsenal.

“Neither I nor the American people would support the sending of an American team to Moscow with Soviet invasion troops in Afghanistan,” Carter said on Meet the Press.

Despite Carter’s claim, both the domestic and international response to the boycott varied greatly. The closest US allies that ultimately joined the boycott were Canada, West Germany, and Israel. Great Britain and Australia also supported the boycott, although both sent athletes to the Games.

In an attempt to bolster support for the boycott in Africa, Carter called upon boxing legend Mohammad Ali to take part in a goodwill tour through the continent to persuade African governments, including those in Tanzania, Nigeria, and Senegal, to join. But the trip fell apart when Ali himself was persuaded to withdraw his support for the boycott during his meetings.

Within the US, public support for the boycott was mixed. The American political elite were united in their support of the boycott, while many Americans sympathized with the athletes who were forced to give up on their dreams of participating in the Olympics.

Furthermore, despite its size, the boycott had no impact on the war, as the Soviet Union remained in Afghanistan until 1989. Since then, the US has not attempted to boycott the Games. Carter went on to lose in the 1980 presidential election in a landslide to Ronald Reagan.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union slowly began planning its retaliation for Carter’s boycott. On May 8, 1984, the USSR announced its intentions to boycott the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, citing “security concerns” and “anti-Soviet hysteria being whipped up in the United States.” Thirteen other Eastern Bloc satellite states and allies joined the boycott,

Despite Soviet officials claiming the boycott was due to security concerns and other similar issues, the boycott was viewed as a retaliatory measure following the US-led boycott in 1980. Nevertheless, 140 nations were still part of the games — a record at the time — while the USSR and its allies hosted the Friendship Games, an alternative to the Olympics.

There have been other boycotts across Olympic history. Taiwan staged the first official Olympic boycott when it withdrew from the 1952 Helsinki Games due to China’s participation for the first time under communist rule. China would go on to boycott the Games until 1980 in protest of Taiwan’s inclusion. During 1984 Los Angeles Games, the IOC made Taiwan compete as compete as Chinese Taipei and under the Olympic flag. This has not changed despite Taiwan being an independent nation.

During the Cold War, Egypt and its allies Iraq and Lebanon boycott the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne in protest over the country’s invasion by Britain, France and Israel during the Suez Canal crisis. Nothing changed.

In 1976, 29 African and Arab countries—including Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guyana, Iraq, Kenya, Libya, and Zambia—boycott the 1976 Summer Games in Montreal in protest against the inclusion of New Zealand, which maintained sporting ties with apartheid South Africa.

In 1988, North Korea boycotted the Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea in anger over not being invited to co-host the event. It was the last full boycott of an Olympic event.

While there were calls to shun the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing and the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi due to human rights abuses in China and Russia respectively, no such boycotts ever materialized. However, this did not stop countries from finding other ways to snub their political rivals.

In 2022, the U.S. announced a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Games, citing “genocide and crimes against humanity” in Xinjiang, a northwestern region of China. The boycott did not affect athletes but precluded government officials from attending the event. Australia, Britain and Canada followed suit thereafter.

It is worth noting that there was no boycott of the 1936 Games in Berlin, Germany, which was then under the control of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party. Some U.S. politicians advocated skipping the Games in protest but the Olympic bodies lobbied against it. At the time, the U.S. Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage called the attempted boycott a “Jewish-Communist conspiracy.”

Meanwhile, the World Cup has faced even fewer boycotts than the Olympic Games. In 1966, all African nations boycotted the World Cup in England because FIFA offered Africa, Asia, and Oceania only one shared qualification spot. FIFA later guaranteed Africa its own automatic slot, which helped open the door for teams like Cameroon, Nigeria, and Ghana in later years.

There have since been calls to boycott the 2022 World Cup in Qatar due to the country’s migrant worker exploitation but that never materialized.

In truth, the vast majority of mega-event boycotts fail to achieve their intended effect. Although they are typically framed as tools to pressure governments into changing policy—by raising global awareness and stripping host nations of legitimacy and prestige—they rarely succeed on those terms. Visibility alone does not translate into leverage. Unless a boycott is paired with sustained economic sanctions, diplomatic isolation, or meaningful institutional exclusion, it remains largely symbolic. By the time a World Cup or Olympic Games arrives, host governments have already absorbed the bulk of the financial and political costs, locked in sponsorships, and secured broadcast deals, leaving them with little incentive to concede under external pressure.

In some cases, the strategy backfires entirely. Rather than delegitimizing the host, international shaming can be repurposed into a narrative of national grievance, reinforcing domestic support and hardening political resolve. This dynamic is particularly pronounced in the United States under Donald Trump, where the administration has openly embraced spectacle and confrontation as instruments of power. Far from being vulnerable to reputational damage, Trump has leveraged America’s hegemonic status to centralize control and project defiance, using external criticism not as a constraint but as proof of dominance.

Interestingly, the most significant pushback to Trump’s policies has come from fellow World Cup co-host Canada. Last week, prime minister Mark Carney made global headlines for a speech in Davos blaming unconstrained super powers for the rupture of the post-WWII world order. Though Carney did not reference Trump by name, the U.S. President responded in his own Davos speech the following day by saying that “Canada lives because of the United States.”

While Trump has made it clear that he no longer views traditional powers like Europe as a partner in his vision for a new world order, there is little evidence of any real appetite on the continent to challenge him—economically, politically, or in the sporting realm. And even the few leaders who recognize what is at stake are unwilling to let that mortality interfere with their most cherished sporting spectacles.

When asked about a potential boycott, France’s Sports Minister Marina Ferrari told reporters that there is “no desire for a boycott of this great competition.”

“The World Cup is an extremely important moment for those who love sport,” she explained.

Boycotts demand backbone, moral clarity, and a willingness to absorb real costs. European leaders have shown, time and again, that they possess none of the three.

Sports Politika is a media platform focusing on intersection of sports, power and politics. Support independent journalism by upgrading to a paid subscription ( or gift a subscription if you already have your own). We would appreciate if you could also like the post and let us know what you think in the comment section below.

Agree! Structurally it seems like boycotts are most effective when it comes to more quantifiable goods e.g. Cesar Chavez and grapes

The 1980 U.S. boycott of the Olympics was one of the follies of Jimmy Carter, a decent man but a mistake-prone president. (We're now enduring a combination of both indecency and mistake-proneness.) The boycott is alluded to in the 1982 film PERSONAL BEST, which was something of a landmark in "lesbian cinema;" and also in women's-sports movies, which scarcely existed all those years ago. The athlete-protagonists are training for the 1980 U.S. Olympic Trials in track and field throughout the film; but as the stadium announcer comments at the end, after the last race, the winners "are all dressed up with no place to go."

The only positive outcome, if one could call it that, is that the Soviet Union's tit-for-tat boycott of Los Angeles in 1984 led to the USA absolutely cleaning up in the medal count, IIRC, given that our mighty, permanent-grudge-match rival was gone, and China was still hardly the sports machine that it would become.

As you know, the slimy Gianni Infantino's flattery of our infant-president with the just-invented "FIFA Peace Prize" has come in for sustained mockery within the United States; it was contemptible. And my enthusiasm for the World Cup, the Summer Olympics, and the 250th anniversary of American independence are all damped-down in the knowledge that our current president will be walking all over them all to claim them as his own personal best.