Did the Pharaohs invent sports diplomacy?

A detailed scene of a wrestling match from the days of Ramses II gives us arguably the earliest example of the political nature of sports, dispelling claims that sport-politics began in Ancient Greece

Welcome to Sports Politika, a newsletter and media platform focused on the intersection of sports, power and politics. This newsletter was founded by investigative journalist and researcher Karim Zidan and relies on the support of readers like you.

If you have not done so already, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

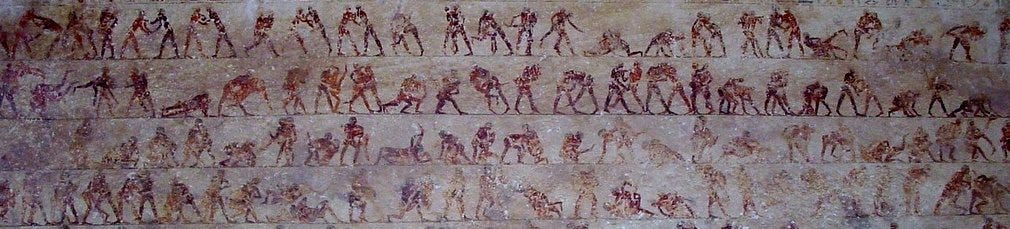

Painted with strokes of reverence and immortalized in pigments of ochre and sienna, an enchanting scene emerges from the Beni Hasan necropolis.

Here, amidst the tombs carved into the high limestone cliffs on the eastern bank of the Nile, lies an elaborate scene of Egyptians wrestlers immortalized in brushstrokes. The wrestlers emerge from the tapestry of millennia, their bodies locked in a timeless struggle of power and grace, a testament to the spirit of competition that thrived in the ancient Nile Valley.

The polychromes and reliefs, many of which were discovered in the tomb of Baqet III, a provincial governor of Menat-Khufu (modern Minya) during the 11th Dynasty, are among the earliest depictions of combat sports and fight culture in Ancient Egypt—a tradition that dates back nearly 5000 years and would continue to evolve through the centuries.

The history of wrestling in ancient Egypt dates back to the Old Kingdom. The earliest portrayals—a depiction of six pairs of boys attempting various grappling holds—was discovered in the mastaba tomb of Old Kingdom Ruler Ptahhotep, who ruled during the 5th Dynasty (approximately 2400 BC). These depictions would become more plentiful during the Middle Kingdom (2000-1780 BC) as more than 400 wrestling scenes were discovered during that period alone, emphasizing the sport’s growing popularity.

Among the most notable examples are the tombs of the aforementioned Baqet III and his son Khety, where wrestling scenes displaying elaborate poses and positions covered much of the walls. The scenes are depicted from left to right and can be followed in a similar fashion to a modern comic strip. However, despite the quantity of scenes depicting wrestling throughout ancient Egypt, information about the rulesets, including legal moves, continues to elude researchers.

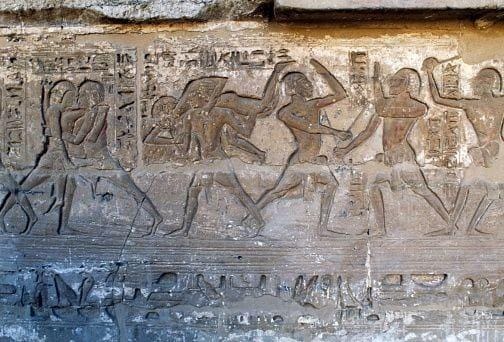

However, arguably the most significant of the scenes was discovered at the temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu, where a detailed scene from a wrestling match from the days of Ramses II gave us arguably the earliest example of the political nature of sports while dispelling claims that sports diplomacy began in Ancient Greece.

The match depicted was between an Egyptian and a Nubian, with Ramses’ international court as the audience. Those in attendance included Nubian diplomats, who watched as their ethnic compatriots are defeated by the mighty Egyptians — a symbolic display of Egypt’s dominance over its neighbors in the region. The final segment in the Medinet Habu frieze depicted a victorious Egyptian wrestler standing over his defeated Nubian foe. The victor is celebrated, while the defeated opponent is forced to acknowledge his loss by kissing the ground before the Pharaoh.

The Medinet Habu frieze shed light on wrestling’s role in political affairs, particularly as a symbol of Pharaoh’s strength and its regional supremacy over neighboring Nubia, even as the latter gained influence.

During the New Kingdom (1546-1085 BC), Egypt increased its military campaigns in the south, sending expeditions deep into Nubia to protect their economic interests and to circumvent tribal chiefs. Following their conquest, Egypt’s Pharaohs divided up and maintained control over Nubia. Pharaohs demanded tribute from the Nubians, including exotic goods, slaves, animals, and minerals. Egypt also used Nubian wrestlers as part of their official sporting events as a form of “imperial exploitation.”.

The earliest such depiction of Nubian wrestlers in Egypt was found at the tomb of Tyanen, an Egyptian officer who died in 1410 BC. The wall painting discovered showed five men marching together with the last man carrying a standard with two wrestlers on it. The Nubian wrestlers are distinguished by their physical characteristics, as they were depicted with more girth than the slim Egyptians.

Another prominent example of wrestling in ancient Nubia can be found in a relief in the rock tomb of Meryre (II), who died in 1355 BC. Meryre was the palace steward of Queen Nefertity, who was married to famed heretic Pharaoh Akhenaton. The painting on the tomb wall shows Phraoh Akhenaton seated on his throne, awaiting tribute from the conquered Nubia.

The presentation also included wrestling matches, which took place before the Pharaoh, his court, soldiers and ambassadors. The match is illustrated from left to right in four frames. The Egyptian is dressed in the attire of a soldier, while the Nubian is mostly naked. Each frame slowly shows the Egyptian soldier overcoming his foe until the Nubian is spilled on the ground in the final frame.

However, the temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu gives us the most prominent example of how sports were used as a tool for diplomacy and regional jousting. This was further confirmed in a letter from an Egyptian official to a Nubian prince at the time, which states: “Be mindful of the day when tribute is brought when thou passest before the king beneath the window, and the counsellors are ranged on either side in front of his majesty, and the chiefs and envoys of all lands stand there marveling and viewing the tribute.”

Though wrestling held evident popularity in ancient Egypt, the Medinet Habu frieze illuminates its significance in diplomatic contexts. Depicted as a symbol of Pharaoh's might, wrestling displays were not merely sporting events but representations of regional dominance, particularly evident in victories over neighboring Nubians.

Moreover, this dispels notions propagated by scholars and journalists that sports diplomacy, or even "sportswashing," originated solely with the ancient Olympic Games. In reality, the utilization of sports as a tool of political leverage by absolute monarchs predates Greek civilization by millennia.

Sports Politika is a newsletter about the intersection of sports, power and politics. If you like what you see, upgrade to a paid subscription ( or gift a subscription if you already have your own). We would appreciate if you could also like the post and let us know what you think in the comment section below.

Fun fact: Beni Hasan’s Beqet III tomb is the oldest depiction in wrestling in the entire world.

Terrific historical description. However, I would like to add that during all of the thousands of years of ancient Egyptian history, there was probably not one wall-painting or stone-carved relief ever made that showed Egyptians losing to a foreigner, no matter what the truth had been. All such artwork was propaganda artwork intended to show off the superiority of Egyptians, individually and collectively, to all foreign enemies. The traditional surrounding enemies--Nubians, Libyans, and "Asiatics," generally people from the modern Middle East--and those from further away, such as the Hittites or the "Sea Peoples" from various points around the Mediterranean Sea.

Rameses III, a fighting pharaoh who reigned for many years, was conspicuously "guilty" of this. In his wars with the Hittite Empire and the Sea Peoples, he is depicted as a giant figure towering enormously over the enemy soldiers, smiting their heads with a deadly mace -- a traditional pose for pharaohs for thousands of years whether they had been in a battle or not. His big battle with the Hittites at Kadesh in modern Lebanon (more or less) is thought by most modern Egyptologists who have ended in a bloody draw followed by a peace-treaty deal. But back in Egypt on the walls of his temples and tomb, the Egyptian artists depicted Rameses as an all-conquering hero and military genius who inflicted a staggering, total defeat on the enemy.

As a result, although the Egyptian wrestlers in the dual meet with Nubia may well have wiped the sandpit with the visiting team, one just can't rely on it as having actually happened. But the bigger thing, the sophistication and popularity of wrestling with the Egyptian court and public, is very true and interesting.

"When the truth. becomes the legend -- print the legend!" (from "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" (1962))

"Untruthfulness didn't begin with us, and it won't end with us." (Russian proverb -- and who would know better about this)

Thank you.