My grandmother, the pioneering artist who captured the universe

A brief interlude from sports and politics...

Welcome to Sports Politika, a media venture founded by investigative journalist and researcher Karim Zidan that strives to help you understand how sports and politics shape the world around us. Our mission is to offer an independent platform for accessible journalism that raises awareness and empowers understanding.

If you share this vision, please consider supporting us by joining our community and becoming a paid subscriber. We are currently running a 20% promotion on annual subscriptions, which you can take advantage of below.

After years of facing death threats and harassment for my investigative work, I learned to value my privacy.

My online persona—the professional identity which most of you recognize from my journalism and social media presence—is carefully curated. I rarely share anything beyond my work. No locations. No deluge of selfies. No personal reflections. No nonsense.

For years, I was fine with this gulf between my digital persona from my physical person. It kept me safe and it kept my family safe. That remains my top priority.

And yet, it recently dawned on me that in order for readers to truly resonate with my work, I needed to offer them the occasional peek behind the curtain. A chance to understand that I am more than the sum total of my articles and investigations; more than just another tweet along your endless doomscroll; more than just the sports and politics guy.

With that being said, I wanted to take this brief interlude from sports and politics to introduce you to another side of me: the grandson of a pioneering Egyptian artist, and the custodian of her estate.

This is the story of how my family and I came to revive Menhat Helmy’s remarkable legacy.

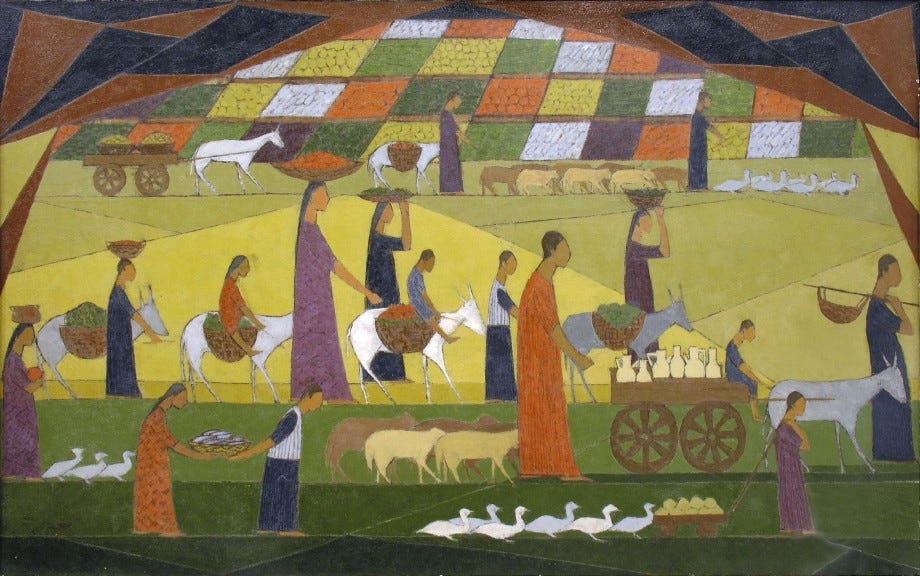

Along the agricultural fields painted emerald, orange, and Tuscan yellow, there stands a procession of workers heading towards The Market (1957). The faceless figures — farmers and peasants; fathers and sons; mothers and daughters — move along the canvas in silence, their paths set in streaks of oil left by the strokes of a paintbrush. Some carry plates of vegetables and meat to sell at the market, others shepherd the animals — goats, cows, and ducks — to their eventual slaughter. It is a painting steeped in colour and life, yet its message is solemn and everlasting: do not forget Egypt’s unseen majority.

As a child, I was mesmerized by this painting. It was my grandmother’s art — Nanaa’s art, as I used to call it. I was far too young to grasp how privileged I was to grow up immersed in such culture; too young to recognize the unique place my grandmother occupied in modern Egyptian art, or understand the profound impact it would have on me as an adult.

I was just 12 years old when Menhat Helmy passed away in 2004. My aunt, Nihal Khallaf, assumed control of her mother’s work. As a successful businesswoman and art lover, she was ideally suited to look after the collection. Realizing the vast potential this held, my aunt decided to host a retrospective exhibition for Helmy’s work, the first since Helmy retired from her profession in the early 1980s. With the help of renowned curator and sculptor Ehab El Laban, the exhibition debuted on December 19, 2005, at Horizon One gallery in Cairo, and was opened by former Minister of Culture Farouk Hosni. Life was good.

And yet, all good things must come to an end.

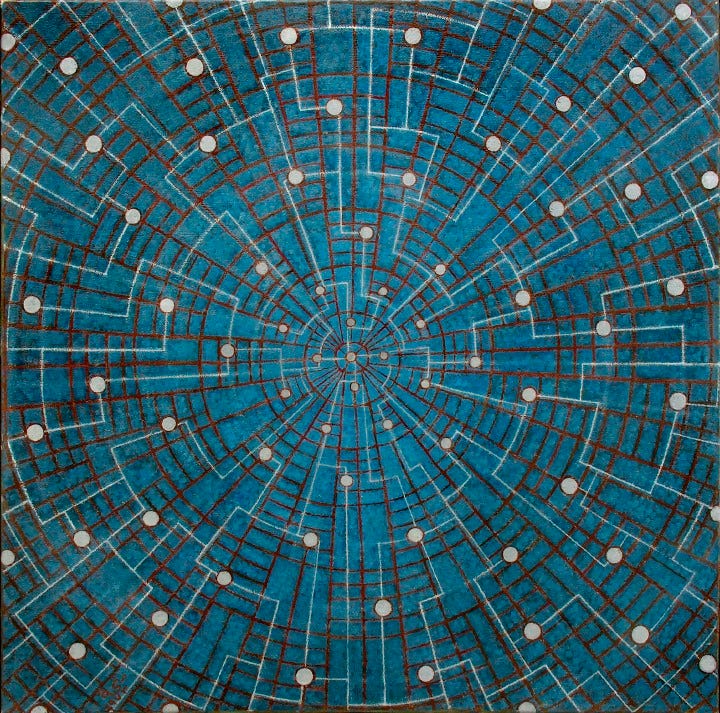

My aunt — the heir apparent to the family legacy — was killed in a car accident in September 2007. Her loss was as sudden as it was devastating. She was the heart and soul of our family, and the fabric that kept us together. Without her, there was nothing left for us in Egypt.

My family, comprised of my single mother and younger brother, left Egypt and immigrated to Canada, taking with us only a handful of my grandmother’s works. I entered university and emerged with a degree in political science and economic development. I became a journalist, got married, and cemented myself in the new world. The only true reminder of my previous life was the abstract etchings hanging on the walls of my apartment. And yet, something called me back to Egypt all those years later — a need to understand my grandmother’s work and to uncover the artistic heritage our family left behind in Egypt.

I returned to Cairo for the first time in seven years in January 2019 with the sole intention of rediscovering my family’s legacy. I visited the old apartment, where the wooden floors creaked and groaned as I made my way down the hall. The walls were yellowed and cracked, while a thick layer of dust rose to greet me with each step I took. The entire space was unrecognizable.

Deciding it was time to take action, I moved the collection out of storage and into another apartment in Cairo, where I had enough room to unpack and catalogue it for future research. As I unboxed the cardboard shells surrounding the art and uncovered the contents within, I was struck by how much of my grandmother’s work I did not recognize. While I recalled the handful of nude portraits, still life paintings, and black-and-white etchings that occupied our home when I was a young boy, I was shocked to find that they made up a small percentage of her overall work. By the time I had finished unpacking the work, I had noted over 70 black-and-white etchings on zinc, 25 paintings, 30 sketches and drawings, 10 lithographs and woodcut drawings, and approximately 60 abstract coloured graphics, many of which were tucked away in old portfolios.

Beyond the actual collection of works, I discovered that my aunt had undergone the tedious process of gathering all the magazines and newspapers that my grandmother had been cited in, dating back to the early 1950s. She repeated this process with all the pamphlets, catalogues, and gallery magazines that featured my grandmother’s work in their exhibitions. Apart from that, there were notebooks, signed guestbooks, journal entries, and endless piles of letters in storage that served as the foundation for my research and the primary tool I used to reconstruct a timeline for my grandmother’s life and work and establish The Menhat Helmy Estate.

Born in 1925 as the middle child in a family of seven sisters and two brothers, Menhat Helmy stood out among her siblings through her artistic talent. She graduated with distinction from Cairo’s High Institute of Pedagogic Studies for Art in 1949 and earned a government scholarship three years later—just months after the July 1952 military coup that overthrew Egypt’s monarchy—to continue her education at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London.

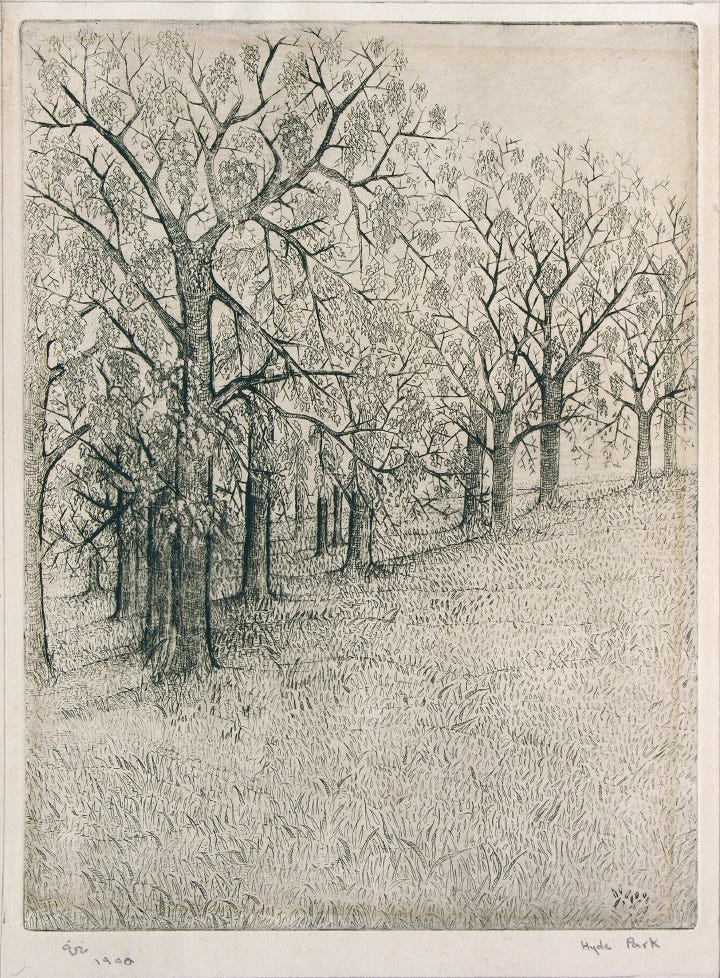

During her three years at Slade, where she studied under the likes of world- renowned sculptor Henry Moore and others like Graham Sutherland and William Coldstream, Helmy focused on painting and graphic printmaking, eventually settling on etchings as her preferred medium. She began to experiment with different plates, using copper, zinc and wood to produce black-and-white prints that distinguished her work at a young age. She journeyed across England during her three years at Slade, exploring London’s parks, churches, and rivers, and traveling to places like the Isle of Wight and to small towns along the countryside. She carried a small sketchbook, which she used to lay the foundations for her later prints. Her dedication to the craft of printmaking did not go unnoticed, as the Egyptian artist—one of the first to attend the prestigious school—went on to win the Slade Prize for Etching in 1955.

Upon Helmy’s return to Egypt in 1955, she found her country engulfed in socio-economic upheaval, geopolitical tension, and revolutionary fervor. Armed with her newly developed skill in etching, she documented the societal changes taking place around her, including the Suez Canal crisis, the historic 1957 parliamentary election, and the building of the Aswan High Dam. In her work, she captured the country’s unseen majority: fishermen on the Nile, laborers in brick factories and animal markets, farmers working the fields. She was one of the first artists to capture the rapidly changing Egyptian State through the eyes of women—whether campaigning to vote, breastfeeding in newly erected outpatient clinics, or as prominent members of society working on par with their male counterparts.

Her work during this time cemented her reputation as a pioneer of Egyptian printmaking.

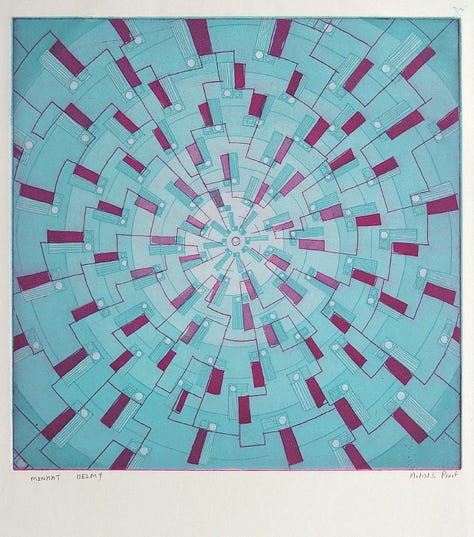

After establishing herself as an award-winning and acclaimed etcher both at home and on the international stage by the late 1960s, Helmy decided to pivot away from the black-and-white etchings that characterized her work, instead challenging herself to create powerful political paintings and abstract prints, the latter of which were ahead of their time in the Egyptian art scene. She completed her pivot towards abstraction, and thus created some of the works that would become her signature pieces. Her black-and-white etchings were a thing of the past, replaced instead by conceptual graphics with complex geometric structures and bright colors inspired by her fascination with the universe, space exploration, technological advancements, and modern machinery.

By the early 1980s, however, Helmy’s lungs began to suffer after years of inhaling fumes from the printmaking process. Then, in 1988, her husband of more than thirty years passed away. Torn from the partner she cherished and deprived of the art that brought her the most joy, Helmy decided to retire. Her final print is dated 1983–a full twenty-one years before her own passing in 2004.

While I cherish my vivid memories of my grandmother and her gentle nature, few revolve around her art. By the time I was born in 1991, she had already retired and was focused on teaching art to a new generation of Egyptian students. Deprived of her creative outlet, Helmy absorbed herself in the role of grandmother. Every now and then, I would ask her questions about her work: Why are those people naked? Why do those people not have faces? Why did you make this in black-and-white? Despite my never-ending childish curiosity, my grandmother never lost her patience, carefully explaining herself in the calm, soothing voice I can still recall.

Though Helmy’s career was cut short by illness, she continued to live her life by the same principles that characterized her geometric works—a penchant for precision, a deep sense of curiosity, and a self-sufficiency that remained steadfast until she departed from our world.

Over the past six years, my mission has been to preserve this legacy. I am proud to say that my family and I have thus far succeeded in doing so.

My grandmother’s work has now been rightfully restored among the pantheon of pioneering modern artists. Her art graces the walls of major museums; her life inspires scholarly research and an entire new generation of artists around the world. And as the custodian of her estate, I consider it my life’s work to ensure that her legacy remains secure for generations to come.

You can help support my mission by subscribing to The Menhat Helmy Estate right here on Substack. From there you can follow the family’s progress with the estate and view a wide range of her works and essays on the socio-political significance of her work.

what a beautiful story, and what a lovely woman she was! thank you for sharing this with us.