African Football and the Long Shadow of Empire

Once a force for decolonization and African pride, the continent's crowning jewel of football—the AFCON—is increasingly beholden to local autocrats and European interests.

Welcome to Sports Politika, a media venture founded by investigative journalist and researcher Karim Zidan that strives to help you understand how sports and politics shape the world around us. My mission is to offer an independent platform for accessible journalism that raises awareness and empowers understanding.

If you share this vision, please consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber.

When Algerian striker Mohamed Amoura scored a blistering winner in the final seconds of extra time at the 2025 African Cup of Nations (AFCON), sending the Democratic Republic of Congo out of the tournament, he added salt to the Congolese wound with a gesture made towards its fans in the stadium.

After scoring the goal, Amoura celebrated by mimicking a stiff, upright pose—a move that has been interpreted as mocking Michel Nkuka Mboladinga, a well-known DR Congo superfan known for standing motionless at matches. His pose is an homage to Patrice Lumumba, the former Congolese Prime Minister and independence hero assassinated in 1961.

Lumumba was a revolutionary independence leader and pan-Africanist who played a significant role in Congo’s transition from a Belgian colony to an independent state. He became Congo’s first elected prime minister but immediately faced a breakdown of order and, eventually, a coup. He was assassinated by Congolese soldiers under Belgian supervision in January 1961, with significant involvement and planning by Belgium and tacit approval from the United States, who saw him as a Cold War threat. At one point, the CIA had plotted his assassination, including schemes like poisoned toothpaste.

Despite his tragic demise, Lumumba was remembered as a standard bearer for decolonization and African liberation, as well as a cautionary tale of the sacrifices that come with challenging the Western overlords. So when Amoura, a fellow African as well as an Arab, mocked the DRC’s national hero, it was seen as disrespectful. He has since apologized, claiming he did not the understand the significance of the superfan’s pose. Nevertheless, it is a reminder of the deep political trauma running through Africa’s veins, and how that inevitably spills out on the football pitch.

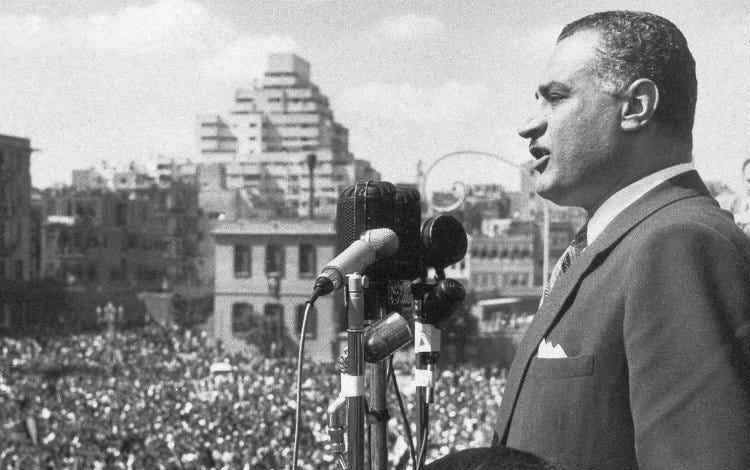

When the Africa Cup of Nations was first held in 1957, it was an inherently political event. In June 1956, on the sidelines of the FIFA Congress in Lisbon, Egypt met with representatives from Sudan, South Africa, and Ethiopia to devise a plan to establish the Confederation of African Football (CAF), the governing body for football in Africa. The organization was a priority for Egypt’s charismatic military leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose “Free Officers” movement had ended Britain’s colonial rule over Egypt in 1952. Nasser viewed CAF and the subsequent AFCON tournament as a powerful propaganda tool that would help unite African nations against their colonial rulers.

In 1957, the inaugural Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) was held in Khartoum, Sudan. There was no qualification process; the tournament field consisted solely of the four founding members of the Confederation of African Football (CAF): Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, and South Africa. South Africa was disqualified after insisting on selecting an all-white squad in accordance with its apartheid policy, a decision that granted Ethiopia a bye directly to the final. As a result, only two matches were played. Egypt was crowned the first continental champion after defeating host nation Sudan 2–1 in the semi-final and Ethiopia 4–0 in the final.

Egypt’s victory carried far more than mere national pride. The country had just emerged from the Suez Canal Crisis, during which British and French forces—acting in concert with Israel—invaded Egypt in an attempt to protect their interests in the recently nationalized canal. The ensuing international backlash forced a humiliating withdrawal, dealing Britain a severe blow to its legitimacy and global standing and marking one of the final nails in the coffin of its imperial ambitions. The fact that Egypt—newly free and independent—had won the inaugural competition so closely associated with decolonization became a powerful symbol for a burgeoning African continent.

Egypt has since continued to make AFCON history. The Arab world’s most populous country has won the event a record seven times, including three consecutive wins in 2006, 2008, and 2010.

However, the country has not managed to reclaim its former glory since the 2011 Arab Spring, which was the same year that Salah first appeared on the national team. Since then, Egypt has reached the finals on two occasions (2017 and 2021). In the 2021 edition of AFCON, Salah’s team came close to winning the cup but fell short in a penalty shootout against Sadio Mané’s Senegal.

Despite the loss, it had been Egypt’s best performance in years. In 2018, Egypt crashed out of the World Cup without winning a single match. The following year, Egypt hosted AFCON but failed to reach the quarter-final stage in a tournament plagued with scandals including accusations of sexual harassment against Salah’s teammate Amr Warda.

While Egypt is no longer as successful as it once was on the continent, countless other African countries attempted to emulate its sporting and political success at AFCON. Over the decades, countless African leaders have utilized AFCON as a tool for propaganda and self-aggrandizement. Among them was Mobutu Sese Seko, the infamous Congolese dictator whose coup ultimately led to Lumumba’s execution. Seko rechristened the DRC as Zaire and went on to establish a violent kleptocracy, amassing grotesque personal wealth at the expense of his impoverished population.

Seko was obsessed with turning Zaire into a sporting superpower. He hosted the 1974 edition of the African tournament, and spent lavishly on infrastructure to support the event and the national team. Zaire went on to win the tournament, though they performed terribly at that year’s World Cup. Seko later hosted the Rumble in the Jungle event pitting Muhammad Ali against George Foreman for the heavyweight championship. It was one of the most watched televised events at the time, breaking countless records.

Seko wasn’t the only dictator to take advantage of AFCON’s prestige. Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya hosted the event in 1982 while Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt won the event four times during his tenure in office. In 2012, Equatorial Guinea hosted the event, which served as international image-laundering exercises for one of the world’s longest-ruling dictators in Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo.

The latest AFCON host, Morocco, has also courted its fair share of controversy. The country, which is ruled by an Islamic monarchy that has reigned since 1631 and claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad, has spent the heavily in preparation for the 2026 AFCON and the 2030 World Cup. That spending resulted in a series of youth-led protests demanding significant improvements to public education and healthcare, while criticizing the government’s spending on football tournaments. Following the protests, the Moroccan government introduced a set of reforms intended to enhance political participation and improve social services.

Morocco is also tied in a long-standing dispute with the Western Sahara, a desert territory annexed by Morocco following Spain’s colonial departure in 1975. The Sahrawi people, an indigenous group native to the region, continue to seek independence, which Morocco vehemently refuses. Morocco administers about 80% of the disputed territory, including resource-rich areas with phosphates and fisheries. Morocco also has a deteriorating relationship with neighbour Algeria, with the latter claiming that Morocco was mining for phosphate on land belonging to Algeria. The border between the nations has remained closed since 1994, complicating matters for Algerian football fans looking to attend the tournament.

The final nail in AFCON’s shift away from its decolonization roots came on the even of the 2025 edition of the tournament, when CAF president Patrice Motsepe announced that would now take place every four years instead of biyearly. When making the announcement Motsepe was flanked by FIFA secretary general Mattias Grafström, a subtle confirmation that the decision was heavily influenced by the European powers at FIFA and UEFA, who hated that clubs had to release some of their most prominent African players mid-season to participate in the tournament.

Africans living on the continent have rarely had the opportunity to watch their star players perform in person. The biennial Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) was one of the few occasions when that aspiration became reality. Most of Africa’s leading footballers are based in Europe, competing in some of the world’s most lucrative leagues in England, France, and Germany. Yet European football authorities deemed even this arrangement unreasonable and exerted pressure on the Confederation of African Football (CAF) to extend the tournament cycle to four years. One could argue that AFCON’s increasing subordination to European interests amounts to a re-colonization of African football.

What began as a nationalist and pan-African project has, in this view, deteriorated into a second-tier event increasingly shaped by forces beyond Africa’s control.

Sports Politika is a media platform focusing on intersection of sports, power and politics. Support independent journalism by upgrading to a paid subscription ( or gift a subscription if you already have your own). We would appreciate if you could also like the post and let us know what you think in the comment section below.